Similar to tort, law recognises certain exceptional conditions in which the act that appears to satisfy the definition prescribed for the offence, nonetheless lacks in certain aspect (generally mens rea or the guilty mind) for it to be punished. The law provides that every definition of an offence, every penal provision and every illustration of every such definition or penal provision shall be understood subject to theseexceptions. Again the idea is to provide lucidity to the large text and avoid repetition. The importance of these exceptions is that once a case falls into an exception, the same does not amount to an offence.

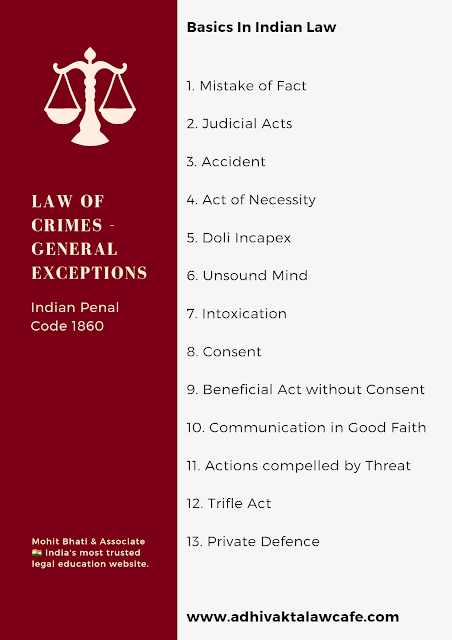

The general exceptions are as follows –

1. Mistake of Fact

The law states that when a person is bound by law to perform any act, his act shall not amount to an offence. It is quite basic that when on one hand the law compels performance, it cannot on the other prohibit it at the same time. This defence is also available where a person by reason of a mistake of fact, and not by reason of mistake of law, in good faith believes himself to be bound by law to do it. That is, the law gives due regard to a bona fide mistake of fact, but not of law. The essential of this exception are –

-

Act is done by a person who is bound by law or

-

Who by reason of a mistake of fact in good faith believes himself to be so bound

-

But not by reason of a mistake of law

Illustrations

-

A, a soldier, fires on a mob by the order of his superior officer, in conformity with the commands of the law. A has committed no offence.

-

A, an officer of a Court of Justice, being ordered by that Court to arrest Y, and after due enquiry, believing Z to be Y, arrests Z. A has committed no offence.

Similarly, if a person is justified by law, or by reason of a mistake of fact and not by reason of a mistake of law in good faith, believes himself to be justified by law, in doing an act, the same is not an offence.

Illustration

-

A sees Z commit what appears to A to be a murder. A, in the exercise, to the best of his judgment exerted in good faith, of the power which the law gives to all persons of apprehending murderers in the fact, seizes Z, in order to bring Z before the proper authorities. A has committed no offence, though it may turn out that Z was acting in self-defence.

2. Judicial Acts

Law gives protection to actions of Judges exercising their judicial powers accorded by the law. The exception also extends to other persons who execute such judicial orders, say warrant of arrest. The scope of exception is not only the exercise of a vested judicial power but also exercise of such power which the Judge believed in good faith to be given to him by law. Thus, law provides for protection to judicial acts and also errors made in good faith.

3. Accident

Act of misfortune or accident are no offence. Though some person may be instrumental in the occurrence of an accident, but if he has acted without any criminal intention or knowledge and does any lawful act in a lawful manner by lawful means and also employs proper care and caution, he cannot be held liable under criminal law for the consequence incurred. Thus, ingredients of this exception are –

-

Act is result of accident or misfortune

-

Act is done without any criminal intention or knowledge

-

Act is lawful

-

Act is done in a lawful manner by lawful means

-

With proper care and caution.

It can be understood that if the above conditions are satisfied, the act cannot be said to have accompanied with mens rea.

Illustration

-

A is at work with a hatchet; the head flies off and kills a man who is standing by. Here, if there was no want of proper caution on the part of A, his act is excusable and not an offence.

4. Act of Necessity

Necessity knows no law. At times, a person may be induced to perform certain detrimental act in order to prevent or avoid bigger harm to person or property. Law provides that if such acts of necessity are done without any criminal intention and in good faith, the same is no offence. Thus, ingredients of this exception are –

-

Act is done with the knowledge that it is likely to cause harm

-

But act is done without any criminal intention to cause harm

-

For the purpose of preventing or avoiding other harm to person or property

-

Good faith

Illustration

-

A, the captain of a steam vessel, suddenly, and without any fault or negligence on his part, finds himself in such a position that, before he can stop his vessel, he must inevitably run down a boat B, with twenty or thirty passengers on board, unless he changes the course of his vessel, and that, by changing his course, he must incur risk of running down a boat C with only two passengers on board, which he may possibly clear. Here, if A alters his course without any intention to run down the boat C and in good faith for the purpose of avoiding the danger to the passengers in the boat B, he is not guilty of an offence, though he may run down the boat C by doing an act which he knew was likely to cause that effect, if it be found as a matter of fact that the danger which he intended to avoid was such as to excuse him in incurring the risk of running down C.

5. Doli Incapex

The term “doli incapex” means incapable of committing a crime. The law provides complete immunity to a child below seven years of age. The law presumes that a child below such age does not have sufficient maturity to understand the nature and consequences of his actions.

For a child between seven and twelve years of age, law provides for conditional immunity. Such a child, who has not attained sufficient maturity of understanding to judge the nature and consequences of his conduct on that occasion, is also covered under the exception.

6. Unsound Mind

The term “unsound mind” is not defined under the law, but it refers to various forms of insanity. The law does not absolve all persons suffering from any kind of mental ailment. But the test is whether the person was, at the time of doing it, by reason of unsoundness of mind, incapable of knowing the nature of the act, or that he is doing what is either wrong or contrary to law. That is, to avail this defence, following must be established –

-

Act is done by a person of unsound mind

-

He is unsound at the time of doing it

-

Incapable of knowing the nature of the act, or

-

What is either wrong or contrary to law

Only if the above conditions are satisfied, the person may claim the benefit.

7. Intoxication

Involuntary intoxication has been recognised as a defence. The law states that nothing is an offence which is done by a person who, at the time of doing it, is, by reason of intoxication, incapable of knowing the nature of the act, or that he is doing what is either wrong, or contrary to law; provided that the thing which intoxicated him was administered to him without his knowledge or against his will.

Thus, the first and foremost condition for defence of intoxication is that it should not be voluntary. Intoxication should have been without knowledge or against will, and the level of intoxication must be such that rendered the person incapable of knowing the nature of the act, or what is either wrong, or contrary to law.

8. Consent

Although crime is an act against society, consent of the intended victim is still a good defence. The defence of Consent basically has three forms. Firstly, it can be given by an adult individual to suffer harm irrespective of benefit. Secondly, it can be given to obtain certain benefit. Thirdly, it can be given by guardian for benefit of a child.

(i) Personal Consent

Man is risk taking and adventure seeking by nature. He has gained a lot by them too. Tiresome sea voyages and finding new lands is prime example of the same. Ancient and Modern day sports have risk elements built in. The law provides that an adult person of sound mind may give consent to suffer risk of harm. The act may or may not be for any intended benefit.But there is alimit to the risk to which a person may consent, that is the act must not be intended or likely to cause death or grievous hurt. Thus, essentials of this defence are –

-

Act is not intended or likely to cause death, or grievous hurt.

-

Person consents to suffer harm.

-

Consent may be express or implied.

-

Person giving consent must be above eighteen years of age.

Illustration

A and Z agree to fence with each other for amusement. This agreement implies the consent of each to suffer any harm which, in the course of such fencing, may be caused without foul play; and if A, while playing fairly, hurts Z, A commits no offence.

(ii) For Beneficial Act

At times, a beneficial act may have an element of risk. But the possible benefit outweighs the risk involved. Surgical treatment is a simple example of the situation, where there is instantaneous bodily harm for a healthy life in longer run. In such cases too, a person may consent to risk of harm. The essential ingredients of this defence are –

-

Act is not intended to cause death

-

Act is for benefit of the person

-

Person has given his consent to suffer that harm, or to take the risk of that harm

-

Consent may be express or implied

-

Act done in Good Faith

Illustration

A, a surgeon, knowing that a particular operation is likely to cause the death of Z, who suffers under the painful complaint, but not intending to cause Z’s death, and intending, in good faith, Z’s benefit, performs that operation on Z, with Z’s consent. A has committed no offence.

(iii) Benefit of Child

Similarly, a benefit for child or unsound may involve some form of harm. In such cases too, the guardian may himself perform the beneficial act or give consent for the same. Essential conditions are as follows –

-

Act is done in good faith

-

For the benefit of a person

-

Person is under twelve years of age, or of unsound mind,

-

Act is done by or by consent of the guardian or other person having lawful charge of that person

-

Consent may be express or implied

This exception is not applicable to

-

Intentional causing of death, or its attempt

-

Act likely to cause death, for any purpose other than the preventing of death or grievous hurt, or the curing of any grievous disease or infirmity;

-

Voluntary causing of grievous hurt, or its attempt, unless it be for the purpose of preventing death or grievous hurt, or the curing of any grievous disease or infirmity;

-

Abetment of any offence, to the committing of which offence it would not extend.

Illustration

A, in good faith, for his child’s benefit without his child’s consent, has his child cut for the stone by a surgeon knowing it to be likely that the operation will cause the child’s death, but not intending to cause the child’s death. A is within the exception, in as much as his object was the cure of the child.

What is not a valid Consent?

A valid consent must be free will of a competent mind. Thus, a consent given under following cases is invalid –

-

Fear of injury

-

Misconception of fact

-

By insane person

-

By person of unsound mind

-

By intoxicated person

-

By Child under twelve years of age.

When consent inapplicable?

The defence of consent is inapplicable to acts which are offences independently of any harm they may cause.

Illustration

Causing miscarriage (unless caused in good faith for the purpose of saving the life of the woman) is offence independently of any harm which it may cause or be intended to cause to the woman. Therefore, it is not an offence “by reason of such harm”; and the consent of the woman or of her guardian to the causing of such miscarriage does not justify the act.

9. Beneficial Act without Consent

Situation may arise where beneficial act must be performed in the larger interest of a person, but such person is unable to give valid consent, nor any other person is available to give consent on his behalf. Thus, its essentials are –

-

Act is for benefit of Person

-

Act is done Without Person’s consent

-

Circumstances are such that it is impossible for that person to signify consent, or if that person is incapable of giving consent, has no guardian or other person in lawful charge of him from whom it is possible to obtain consent in time.

-

Act is done in Good Faith

This exception is not applicable to

-

Intentional causing of death, or its attempt

-

Act likely to cause death, for any purpose other than the preventing of death or grievous hurt, or the curing of any grievous disease or infirmity;

-

Voluntary causing of hurt, or its attempt, for any purpose other than preventing of death or hurt;

-

Abetment of any offence, to the committing of which offence it would not extend.

Illustrations

-

Z is thrown from his horse, and is insensible. A, a surgeon, finds that Z requires to be trepanned. A, not intending Z’s death, but in good faith, for Z’s benefit, performs the trepan before Z recovers his power of judging for himself. A has committed no offence.

-

Z is carried off by a tiger. A fires at the tiger knowing it to be likely that the shot may kill Z, but not intending to kill Z, and in good faith intending Z’s benefit. A’s ball gives Z a mortal wound. A has committed no offence.

10. Communication in Good Faith

No communication made in good faith is an offence by reason of any harm to the person to whom it is made, if it is made for the benefit of that person. That is –

-

Communication is made to a person

-

Communication is for the benefit of that person

-

Communication is made in good faith

Illustration

A, a surgeon, in good faith, communicates to a patient his opinion that he cannot live. The patient dies in consequence of the shock. A has committed no offence, though he knew it to be likely that the communication might cause the patient’s death.

11. Actions compelled by Threat

The evil in man can sometimes take form of threat. That is, a person may not perform wrongful act himself, but compel other to do so. In such cases, the person acting lacks required mens rea and law provides exception for him. The essential ingredients for this defence are –

-

Person is compelled to do the act by threats

-

Threat is made at the time of doing the act

-

Threat gives reasonable apprehension of instant death

-

Person has not placed himself in such constraint

-

Defence is not available to offence of murder and offences against the State punishable with death

12. Trifle Act

Where an act causes or intended to cause or known to be likely to cause any harm, which is so slight that no person of ordinary sense and temper would complain of such harm, the act is covered under the general exception of trifle act. The same amounts to no offence.

13. Private Defence

Every person has right to defend his life and property against unlawful aggression. Every person has a right, to defend—

-

His own body, and the body of any other person, against any offence affecting the human body

-

Any movable or immovable property, of himself or of any other person, against offence of

-

Theft,

-

Robbery

-

Mischief

-

Criminal trespass

-

Attempt of any of the above

-

The right of private defence is quite elaborate and even extends to causing death of aggressor in certain circumstances. Right of private defence of body extends to causing death of the assailant, where the assault is with intention of or reasonably cause apprehension of –

-

Death

-

Grievous hurt

-

Rape

-

Gratifying unnatural lust

-

Kidnapping or abduction

-

Wrongfully confinement where there is apprehension that he will be unable to have recourse to the public authorities for his release.

-

Act of throwing or administering acid with apprehension of grievous hurt

Right of private defence of propertyextends to causing death of the assailant, against the following offences–

-

Robbery

-

House-breaking by night

-

Mischief by fire committed on any building, tent or vessel, which building, tent or vessel is used as a human dwelling, or as a place for the custody of property;

-

Theft, mischief, or house-trespass, with reasonable apprehension of death or grievous hurt

But the right of defence is limited to exercise of defence. It cannot take form of offence or aggression. Thus, the right begins with the threat and continues till the threat continues. Once the threat comes to an end, so does the right. Further, the harm that may be inflicted as defence, must be proportional to the threat.

Illustration

A, a gunda, assaults B by pointing a knife at him. B takes out a pistol. B commits no offence by showing the gun, though he has a definite advantage over knife. But B may not shoot A, unless the threat is innature ofimmediate death or grievous hurt. Further, ifA is alarmed and effects retreat, the right of private defence comes to an end.